Bald Black Girls Reign in Sutoyé’s Barbershop

A note on timing:

I started writing this piece in April, 2019, as an assignment for Uni. Then my mum got sick and passed away, and everything was set aside. Earlier this year, I came back to this, and decided, despite the time that had passed, to finish it anyway. Then of course, to quote a friend 'a literal plague' happened. I did finish it, though, and finally, here it is.

Bald Black Girls Reign in Sutoyé’s Barbershop

words and images by Wasi Daniju

13 April 2020

“I think I was seeking a community, I didn’t know I would create one’.

Ruth Sutoyé, artist and co-curator of Bald Black Girl(s).

|

Installation view of Bald Black Girl(s), 13 April 2019, Unit 5 Gallery, London. © Wasi Daniju |

The first time I shaved off all my hair 8 years ago, a male friend told me women only do this as a sign of mourning. My mother told me that in Islam, a shaved head was reserved for men. As for my own intentions - it was simply a liberation from the time and energy required to maintain my hair well, and a desire to try something new. For me, there was never anything political or symbolic about it, not consciously, at least; as with so many of the choices women make about their appearance, though, it was imbued with significance by those around me - as Susan Sontag once wrote, ‘[w]omen are judged by their appearance as men are not…’, and with Black women, the matter of our hair is often politicised, no matter our intention. Whether it be girls in South Africa fighting for the right to wear their natural hair to school, Black women’s hairstyle choices at work being a matter for HR, or even news coverage of the first Black woman elected to congress, Ayanna Pressley, not for her political achievement but specifically because she chose to wear her hair in Senegalese twists, it seems we will not be free of judgement on our choices any time soon. |

The penultimate time I shaved my head, in April of last year, it was following my mum’s diagnosis of Leukaemia - perhaps some sort of pre-emptive mourning of her death two months later, but at the time, a demonstration of solidarity with my mother as she feared losing her hair during treatment. Ironically, throughout her illness, despite many other losses, that particular fear was never realised, and she was buried with the last hairstyle I plaited for her.

|

Audience member taking a photo of one of the images from the Bald Black Girl(s) exhibition. 13 April 2019, Unit 5 Gallery, London. © Wasi Daniju |

On April 13 2019, a year ago today and three days after the launch of Bald Black Girl(s), a Curators in Conversation event was held in the exhibition space at London’s Unit 5 Gallery, allowing attendants to not only view and interact with the work, but also a chance to hear from and dialogue with Sutoyé, and her co-curator, Aliyah Hasinah.

Artist and curator Ruth Sutoyé (left) and co-curator Aliyah Hasinah (right) introduce each other at the Bald Black Girls Curators in Conversation event.

13 April 2019, Unit 5 Gallery, London. © Wasi Daniju

Sutoyé and Hasinah open the event with an encouragement for those present to ask questions throughout, to ‘co-create a dialogue'. They note that while this is often said but not truly meant at events such as these, here it is sincere. It seems the audience, almost exclusively Black women, many of whom are ‘bald’, take this to heart; Sutoyé and Hasinah both speak with a very apparent warmth and candour about the work, themselves, and each other, and this is returned by the crowd gathered to hear them. As in the audio installations which make up the aural section of the exhibition, the group in attendance here share their own stories around issues of gender, identity, beauty standards and more. A number talk about their experiences when they first cut or shaved their hair - reactions from family, harassment and discomfort in barbershops, assumptions from strangers, and their own feelings about their choices.

One thing that comes up during the conversation is a clarification on terminology; the exhibition uses the term ‘bald’ to describe women with shaved and low-cut hair, as well as those who are bald through hair loss, a fact I learnt due to the project. Through conversations with various Black women and non-binary folk since, I’ve come to learn that this is not necessarily a universal understanding - for some, the term ‘bald’ retains only the meaning of no hair at all, whether or not this is voluntary. Whatever the case, across various Black communities, ‘bald’ is rarely used solely to mean involuntary hair loss.

|

Audience member looks at images from Bald Black Girl(s) 13 April 2019, Unit 5 Gallery, London © Wasi Daniju |

An example of the tone of the event: one audience member shares her difficult experiences with her family following her choice to shave her head, and receives empathetic responses from others in the room, with Sutoyé commenting that ‘this feels like a big group therapy session’. Another woman turns to the one who had shared her experiences and simply tells her ‘you’re not alone - look all around you’. This, for me, is the epitome of what Sutoyé’s work has achieved - an avenue for bald Black womxn to see themselves and share their experiences in a space where those experiences are readily understood and reflected.

|

Audience member, actor and dancer Anna-Kay Alicia Gayle. 13 April 2019, Unit 5 Gallery, London. © Wasi Daniju |

Sutoyé and Hasinah demonstrate an exuberance coupled with a deep nuance and careful thought in each of the questions they ask and answer of each other. They manage to bring another layer to the work as they share their process, from details of the genesis of the project to the meticulous care applied in bringing together and amplifying the many different voices of the womxn involved into an exhibition which allows for what Hasinah refers to as a ‘multiplicity of narratives’.

In amongst the talk of identities - gender, blackness, queerness - Hasinah, Sutoyé, and members of the audience, speak of how these aspects of their selves affect the way in which they participate in and experience the art world, and the ways in which they decide to create their work. The women present share recognition at the experience of being followed in art galleries, of not seeing themselves in the art they often see in ‘mainstream’ spaces, and the various acts of micro-aggression and erasure that continue to happen to them in so many incidents of engaging in the art world. A crowd member speaks of the importance of not allowing the fear of what may happen in predominantly white institutions to stop Black people, especially younger people, from attending, or causing them to believe that the spaces are ‘not for us’.

Sutoyé and Hasinah both speak of the importance for them of creating work specifically ‘for Black womxn’ - ‘womxn’ being an alternate spelling of ‘women’, which is employed in the exhibition description.

|

| Artist and curator Sutoyé expands on a point. 13 April, 2019, Unit 5 Gallery, London © Wasi Daniju |

Reign, the short poetry film created for the exhibition, imagines a world in which only bald Black womxn exist. Sutoyé describes it as ‘an imagining, a possibility’. She talks of one white attendant at the launch of the video approaching her to say they found the work ‘confrontational’. The crux of their argument, Sutoyé explains, “this person felt intimidated by a world in which they did not feature, an imagining of a place in which they were not only not centred or in the majority, but not in existence at all.” Sadly, in my experience, this is too often a reaction to the creation of work and spaces that centre Blackness - Black Lives Matter continues to be read by certain white folk as a divisive campaign, comparable to the Klu Klux Klan, as reported in a recent episode of the Gimlet Media podcast, The Nod; while every Black History Month still comes with a chorus of voices that call it out for being exclusive. As a photographer whose focus is on creating work that, amongst many other things, reflects my Blackness, I have also faced similar questioning. I’ve moved from being annoyed or surprised to skipping straight to taking it in my stride - in a majority of the cases, the questioning comes from a similar feeling of intimidation as that of the person who was disturbed by Reign, and I’ve realised it is not for me to calm this anxiety.

Walking around the room, and listening to Hasinah and Sutoyé speak of their intentions with the work - to present the many and various facets of Black womxn who are bald or low-shaved - I am struck by the elements of self portrait. While Sutoyé does not appear directly in the work, I find it impossible to extract her from the images she has created, and the stories she relates. As Sutoyé points out to one attendant who asks why she does not feature in the photographs, the whole of the work is a portrayal of her self.

I am reminded of Zanele Muholi’s ‘Faces and Phases’, in which she commemorated and celebrated the diversity of Black lesbians and trans men in South Africa. Muholi described this work as ‘at once a visual statement and an archive’. She further stated:

|

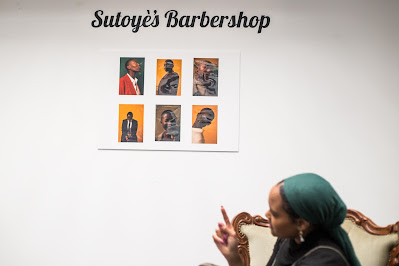

| Curator Aliyah Hasinah discussing Sutoyé's Barbershop. 13 April 2019, Unit 5 Gallery, London. © Wasi Daniju |

“My photography is a therapy to me. I want to project publicly, without shame, that we are bold, Black, beautiful/handsome, proud individuals”. Without a doubt, this is the feeling I am left with from Sutoyé’s work, the conversation between the two curators and the contributions of all of those in attendance. This work and this space are sites of self-celebration as much as anything else.

As talk turns to the experiences of Black women in barbershops, I cannot help but think of the work of Faisal Abdu’Allah, whose craft of barbering frequently informs his art, perhaps most directly in his Live Salon, where he barbered Black men’s hair in a salon created as an exhibition space within an art gallery. Abdu’Allah’s website describes an integral part of this work as being ‘the intimate relationship between customer and barber, the close conversation between two men that is inherent in the unquestionably masculine zone of interaction on the barbershop floor’. The purportedly inherent masculinity of the barber shop, also central to Inua Ellam’s play the Barber Shop Chronicles, is questioned and critiqued in Sutoyé’s work, and the day’s discussion involves a sharing of experiences, both negative and otherwise, that women present have had in barber shops, as well as recommendations for good barbers!

Fast forward for a moment to April 2020 and the UK lockdown due to Covid-19; social media feeds feature an array of newly bald Black girls, as not only barbershops but also hair salons have become inaccessible to all due to the current situation. I too have joined this trend, my most recent crop once again for the sake of practicality. I wonder if this very specific situation might add yet another strand to the multiplicity of the Bald Black Girl(s) narratives.

In response to the final question from the audience on the day, which asks if anything surprised Sutoyé about the project, she talks of how it ‘literally took over my life’, and how she hadn’t realised that it would. She was also surprised that a project so dear to her own heart would be so fully embraced and related to by so many others. She tells us ‘I think I was seeking a community, I didn’t know I would create one’. As the event draws to a close, it is quite clear that in Bald Black Girl(s) Sutoyé has created a work that sings with truth and vulnerability, and with it, perhaps inevitably, the community sought by herself and so many others here today, this writer included.

|

Sutoyé and Hasinah after the event. 13 April 2019, Unit 5 Gallery, London © Wasi Daniju |

References

Abdu’Allah, F. (No date). Works in Focus. http://faisalabduallah.com/content/uploads/Faisal-Works-in-Focus.pdf

Eddings, E (2018) The Nod [Audio podcast]. http://gimletmedia.com/shows/the-nod

Sontag, S in Leibovitz, A, Sontag, S (2000) Women, London: Jonathan Cape

Women's Resources and Research Center (No date). Hxrstory of WRRC. https://wrrc.ucdavis.edu/about/hxrstory

Muholi, Z (2014) Faces and Phases 2006 - 14. New York: Steidl Publishers, The Walther Collection

Comments

Post a Comment